In other articles I have reviewed evidence associating kidney stones with high blood pressure and kidney disease. One might well extrapolate from these two associations that stone forming will also associate with vascular complications such as stroke and myocardial infarction. High blood pressure and kidney disease are well known risk factors for both.

In other articles I have reviewed evidence associating kidney stones with high blood pressure and kidney disease. One might well extrapolate from these two associations that stone forming will also associate with vascular complications such as stroke and myocardial infarction. High blood pressure and kidney disease are well known risk factors for both.

In fact, this is true. Forming stones associates with higher risk of both stroke and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) – commonly called heart attack – when compared to people free of stones.

These associations do not say that stones themselves cause high blood pressure, or stroke, or AMI, merely that people who form them have higher risks of vascular disease leaving unsaid what might be the matrix of causes involved.

The painting Filial Piety, The Paralytic and his Family, was painted in 1763 by Jean Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805). It hangs in room 288 of the WInter Palace of the Hermitage museum. Catherine II (The Great) purchased it from the artist through the advice of Denis Diderot. Diderot (1713-1784) was a French Enlightenment philosopher famed for his metaphysical and ethical thinking. Although his writings brought him little money, Catherine provided for him through her purchase of his library and support of a house during his life.

Acute Myocardial Infarction

Olmsted County

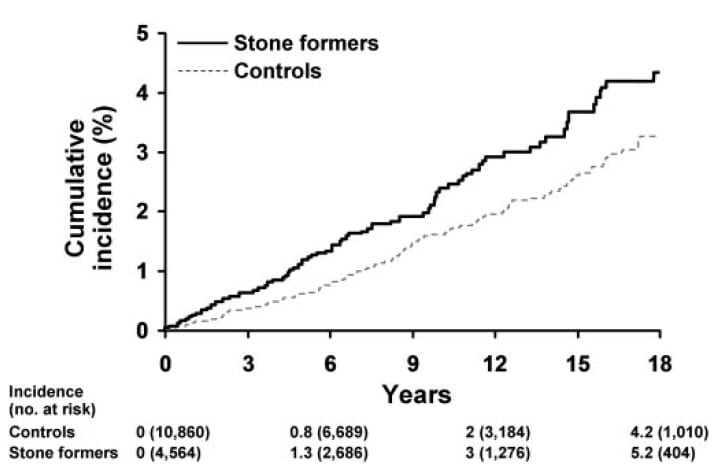

Rule and his colleagues have access to records from Olmsted County wherein resides Mayo Clinic at which a majority of the people living there obtain their care. They used all patients identified between 1984 and 2003, asking if history of kidney stones raised risk of AMI.

The graph shows their result; those with stones had the higher incidence (onset) of AMI. Statistical analysis yielded a relative risk of 1.43 (95% CI 1.11-1.84). Adjustments for age and sex, and for alcohol dependency did not abolish the significance of the increased risk.

The numbers show how many controls and stone formers were in the population at baseline, and after various times (mean of observation years) of prospective observation.

WIthout parsing all of the details, their final summary was that stone formers had a 38% risk increase in AMI that may well arise from shared risk factors for both stones and AMI such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and lipid abnormalities. But increased risk of AMI remained significant despite adjustment for all of these.

Even though risk for AMI remained after adjusting for them, it is interesting to me that compared to non stone formers the stone formers had increased prevalence of all of the above risk factors. Time will sort out the many causal linkages involved.

Alberta Canada

Between 1997 and 2009 the universal health care system registered 3,195,452 people for whom Curhan and his colleagues gleaned a median follow up period of 11 years. They excluded people on dialysis or who had a kidney transplant, and who lacked at least 3 years of observation dating from their 18th birthday, April 1997, or registration in the health system and ending March 2009, when the study period ended. They calculated the relative risk for first AMI during follow up. Being good epidemiologists they also considered death from cardiovascular disease, and need for coronary angioplasty or bypass, and occurrence of stroke.

Their cohort included 1,834,612 people with no measured serum creatinine, so they formed two groups: one with everyone in it who had adequate preliminary baseline health data as above, and a smaller group who had at least one serum creatinine level so they could assess kidney function. For simplicity, I show their large cohort.

At the top of this figure is the hazard ratio (risk ratio) for AMI, stone former vs. non stone former. Overall, top point, stone former risk was 1.4 times controls, and the lower 95% bound was 1.3 meaning this is not likely from chance.

Most remarkably, the increase in risk was highest among younger people, women vs. men, non diabetics, people without hypertension or prior cardiovascular disease.

The Charlson score is a sum of bad things that can afflict people: AIDS/HIV, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, lung disease, dementia, diabetes, heart failure, liver disease, prior AMI, paraplegia, peptic ulcer, peripheral vascular disease, and rheumatological diseases. AMI risk rose as this score fell.

So stone forming associates with increased risk of AMI especially in healthy young women. It is absent in people older than 70, in diabetics, those with cancer, and borderline in people with hypertension.

The Harvard Cohorts

Elsewhere I have shown the outstanding work on urine risk factors and supersaturation based on long term observations of three (two female and one male) health professional groups. Curhan and colleagues used their three cohorts to ask about risk of AMI and coronary revascularization rates.

Their paper has no pictures so I would have to make one. I decided not to as the key results are easy to capture in a few numbers. Among the younger of the two female cohorts, the fully adjusted hazard ratio for AMI was 1.42 (1.07-1.90, 95% CI), and almost the same, 1.23 (1.07-1.41) in the older female cohort. Among the males adjusted values did not differ significantly from 1.0.

Taiwan

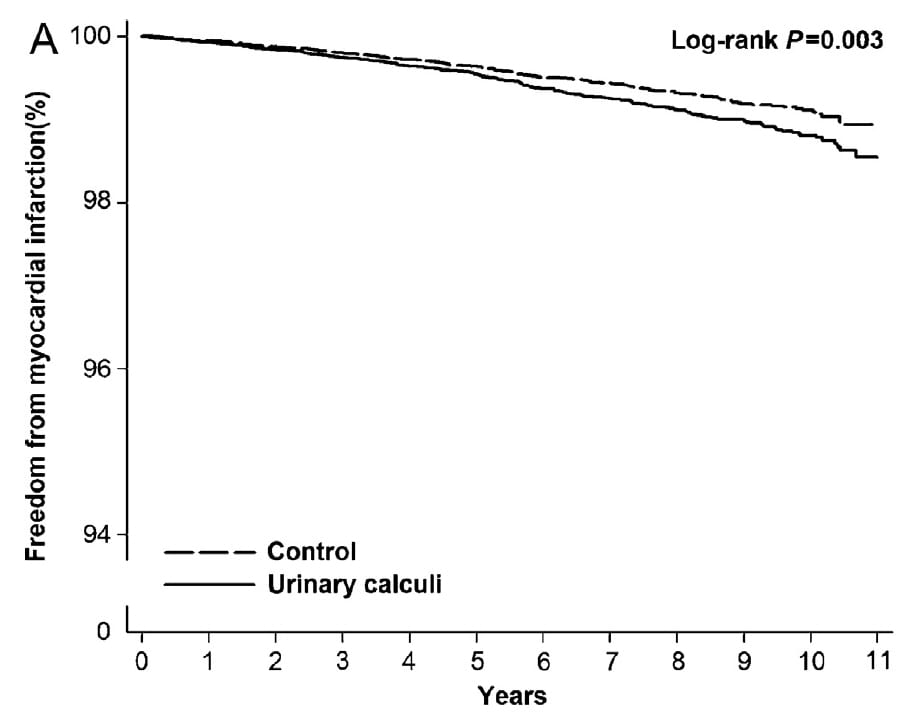

Using a random sample of 1,000,000 people drawn from from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, Hsu et al measured AMI onset over a 10 year period and used life table Cox analysis to determine association with stones.

Those with stones had an increased risk as shown by the reduced AMI free percentage. The hazard ratio was close to that of other studies 1.31 (1.24-1.55). But the sex difference was different here than in the other studies: For males the HR was significant in men, 1.35 (1.11-1.65) but not in women, 0.93 (0.62 – 1.38).

Stroke and Cardiovascular Disease

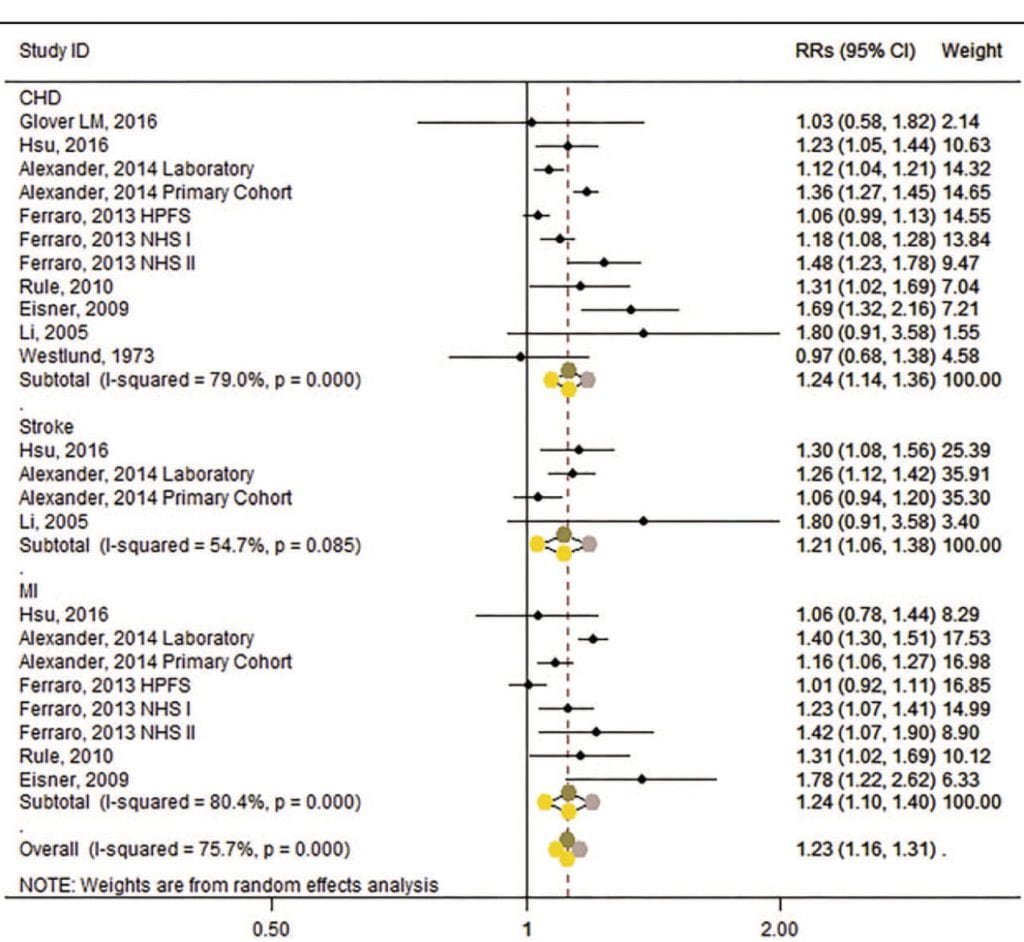

For all cardiovascular disease and stroke, I find this meta – analysis convenient as it has in it the main studies and does a fair enough job presenting the data. The one useful figure from the paper is large, but the message is also clear: Risk is slightly higher in stone formers for stroke as for AMI and – given they are a large part of cardiovascular disease – for total cardiovascular disease as well.

The figure includes those I already presented as well as several I did not detail separately.

The overall message is an increased risk for all cardiovascular (CHD) disease (1.24), stroke (1.21) and AMI (1.24). There is considerable heterogeneity between studies (the I-squared values are much above 25%) and when viewed in aggregate the overall risk increase modest. But even so, unmistakable.

In a separate analysis I do not copy here, they found that overall risk of AMI was high only in women, CHD in men not women, and that AMI was not increased significantly in Asian studies taken in aggregate, even though the large and recent study from Taiwan was quite impressive.

Concerns About The Meta-analysis

The Li study (listed for CHD and stroke) used a stroke registry in Malmo Sweden and focused on those with stroke who had no evidence of hypertension prior to the stroke. Using regression analysis they identified present smoking, high BMI and high normal diastolic BP as well as prior CVD as correlates of stroke. History of stones was included but not significant, 1.8 (0.91-3.58). Because it did not concern stones but found them, as it were, rummaging about, may be imprudent, even if formally acceptable to pool this with the others.

The Glover study authors simply interrogated NHANES 3, a national health survey, asking for any relationship between kidney stones as a response to one of the questions asked of participants, and 10 year risk of future cardiovascular events. Risk was increased by stones in blacks.

But how was risk determined? It was estimated from the Pooled cohort equations risk calculator that uses risk factors – like cholesterol – to predict. So, these writers compared calculated 10 year risks with and without ‘yes’ to a question about stones. This highly indirect estimate is pooled into real science using large databases that give real outcomes but perhaps should not have been.

The Main Message

One has trouble denying some real association here between being a person who forms stones and having a small increase in risk for AMI, stroke, and CVD in general. Of greatest interest, the increase of risk is most discernible in early middle age, and in women. I suspect this is because stones confer only modest increase of risk but do so earlier than most other factors that act either later in life or cumulatively with age.

The Enigma of Cause

How stone forming does this lies beyond my imagination, even if it is true that I know perhaps more about kidney stones than the average scientist and have, therefore, a richer substrate to imagine out of.

If pushed for a vision, a dream, a possible mechanism, I would have to say some people are genetically unsuited to our diet and respond with a mixture of stones, bone disease, and vascular disease that occur in variable proportions between the sexes. That has, at least, the virtue of making a powerful prediction if to a difficult and expensive experiment: Modification of key diet factors, sodium, potassium, calcium, refined sugar, and perhaps protein sources should reduce onset of vascular events such as AMI more in stone formers than in matched controls.

I realize my proposal is not practical but offer it as a starting point.

The Clinical Point Now

Offer, and Eat the Kidney Stone Diet

While we wait for a next step, physicians and patients can be prudent and take actions that are aimed at stone prevention and maybe at reduction of CVD: Diet changes as I just mentioned. They are to move toward the kidney stone diet, which means the present ideal US diet. This applies to every stone former whose stones are not arising from systemic diseases. Given it is in the general health interest of all physicians to promote this diet, it being established for the US population, I have no compunctions, no reservations about urging action.

Not only patients, but their family members would be wise to change toward this diet. In fact, the physicians who care for stone formers might be equally as wise to do this, and everyone else, too. What does it mean when large numbers of experts tell us to eat a certain way, for reasons as sound as we can have presently, and physicians demur?

Thiazide Diuretics Lower Risk of Death from CVD

These drugs lower urine calcium and we use them commonly for stone prevention. In multiple trials conducted over decades they have been successful in lowering blood pressure and reducing death from stroke, heart failure, and AMI.

Be Alert to Modifiable Risk Factors

Blood pressure, serum lipids (though I have always had reservations about their predictive role), bone mineral density, body weight and BMI, exercise and general cardiovascular fitness – these matter for everyone but especially for people who have formed a stone. It is as if we have been given an extra warning, patients and physicians alike, and choose to ignore it, or play it down.

We have enough associational evidence to take seriously the idea that any stone former is at risk for significant systemic disease that has modifiable risk factors. Changing them is good sense, and without known risk.

I wish to thank Dr John Asplin for his careful reading and corrections to this article.

Hello Dr. Coe, Thank you for this informative site. I am a 36 year old female, and have been having recurrent calcium phosphate (hydroxyapatite) stones for at least 10 years. My first stone was a 10mm stone in my ureter, and over 30 additional 8mm+ stones were removed during that surgery. Numerous ESR’s over the years. 24 hour urine in 2010 indicated Hypercalciuria, Hyperuricosuria and Low urine volume. A subsequent test in 2017 was normal results. However, since 2017, my stone burden has increased exponentially, and now it appears I have nephrocalcinosis. My blood pressure has increased over the last 2 years as well – but was always normal. I’m a non smoker, BMI 23.0, and take gabapentin and duloxetene for restless legs/skin crawling sensation (nerve function tests normal). Would you be concerned with the higher blood pressure along with the increased stone burden? My urologist has asked me to consult with the University of Minnesota, which will take place in 2 months. Thank you!

Hi Jessica, I would be concerned about the blood pressure, and would want it treated. Likewise the increasing stones. Of what you mention the low urine volume seems most worrisome, and the high urine calcium would need special attention. Mike Borofsky is the person at Minnesota, I would suggest you see him and make that a special request. He is very skilled in stone management. Regards, Fred Coe

Namste. Myself aniket from india, on 28th December 2019 my uncle died due to sudden cardiac arrest in hospital while he undergoing treatment for kidney stone. On 26 December doctor performed laser operation for kidney stone and patient supposed to discharge on unfatful day. My uncle was farmer by profession and had health lifestyle, diet but never had heart related problem , i just google topic of kidney stone and cardiac arrest and arrive here to share this incidence.

Hi Aniket, I am very sorry about your uncle. Sudden arrest may arise because of unsuspected underlying heart disease or perhaps was directly related to the surgery. We cannot know for sure. My sympathies to you and your family. Regards, Fred Coe

Hello Dr. Coe,

I am 58 years old, have cystine stones, had surgery on my left kidney, multiple procedures on both and currently have 3 stones in my right kidney and now high blood pressure. I am wondering the best approach to control my blood pressure. Do I involve a nephrologist, urologist, or cardiologist along with my primary doctor? Are there preferred medications that are kidney friendly (especially for cystine stones) to treat high blood pressure?

I had the privilege of meeting with you about 20 years ago while having stones and just having my daughter. You enabled me to raise my daughter and enjoy my life at such a scary time. You’re my hero! Thank you!

Hi Lisa, I believe my prior note answered this. I would seek expert consultation as noted. Best, Fred Coe

Hi Dr coe I really appreciate your findings true as I am suffering from stroke and heart attack along with kidney injury although the treatment where I have question could there be chances that I have been taking treatment from 3 months may be due to high doses of medications for infection of kidney stones could have damaged the nerves in brain as I had similar experience earlier when I was drown down in a river and brain nerve damaged. As I m doing my self treatment using my earlier medications for the above disease.

Hi Abhishek, Most antibiotics do not damage the brain, so I would hope that whatever happened is not due to medication. That you have had brain, heart and kidney damage and mention infection from kidney stones, was the infection possibly a cause of the other problems. That can happen. Regards, Fred Coe