by Dr Fredric Coe | Sep 1, 2016 | For Doctors, For Patients, For Scientists

Here are all the trials for prevention of idiopathic calcium stones, and my personal approach to using their results in clinical stone prevention. The whole site thus far has been built to support this article, which is the capstone of the enterprise. To highlight its importance I have made it header type larger.

Beside the usual references, I provide spreadsheets that contain all of the trial stone data with links to the original articles and PDF images of the articles. I also provide spreadsheets of stone risk data from the trials that I use in my analysis of the physiological responses to treatment. So this is a definitive as I can make it. I have left the two preceding videos in red because they are the steps up to this article, and perhaps people might want to view them in preparation. The two prior articles on phenotypes that come before the videos are also preparatory to this final presentation.

I say final because with the full presentation of all of the trials we have more or less covered the entirety of idiopathic calcium stone disease and need to move on to other stone types and to the systemic diseases that cause stones.

by Dr Fredric Coe | Aug 30, 2016 | For Doctors, For Patients, For Scientists

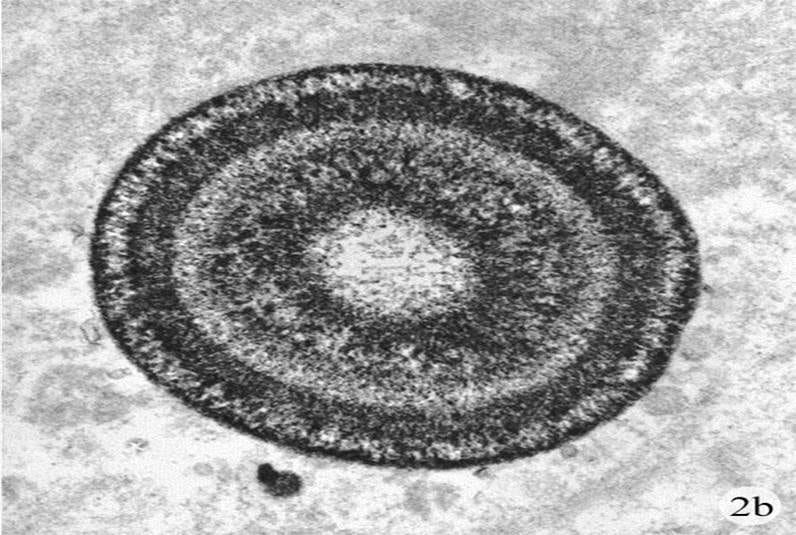

With considerable trepidation, I unfurl my first and certainly very unpolished video offering. The good part of the articles on this site is their devotion to scientific accuracy and referencing from PubMed. The bad parts are their opacity, length, and difficulty. I have long been a public lecturer and decided that video offerings might be a valuable add on. There is more room, I think I speak better than I write, and it seems to me one video can summarize and complement a group of written articles, so I did this one. It covers crystal formation, how crystals are made, and where in the niches and crevasses of the kidney they actually form. Its message is my usual one: Prevent crystals and you prevent stone disease. This is a beta version. I know it has some errors in it. I also know it lacks refinements I need. But, refinements and corrections will come. Let me know.

by Dr Fredric Coe | Aug 29, 2016 | For Doctors, For Patients, For Scientists

Here is the most common kind of stone former, described in such detail as one can muster up at this time. They are simple to diagnose: Stones containing a preponderance of calcium oxalate, no uric acid, struvite, cystine, brushite, drugs, or rare organic materials, and exclusion of any systemic disease as a cause of stones. More or less, these patients are stone disease as it is seen in primary care and most urology practices. Of the millions of stone formers most are like this. The trials for prevention of calcium stones have mainly used these patients as a majority of subjects. However common they may be, and easy to define, they are complex in the way that they make stones, and it appears that there may be not one but perhaps two kinds of idiopathic calcium oxalate stone former. Because of modern flexible ureteroscopy the types of idiopathic calcium oxalate stone former will soon be told apart during stone removal surgery, and patients and their physicians confronted with a variety they may not fully expect. This article sums up what is known, as best as I can manage.

by Andrew Evan | Aug 28, 2016 | For Doctors, For Scientists

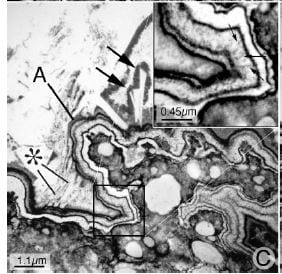

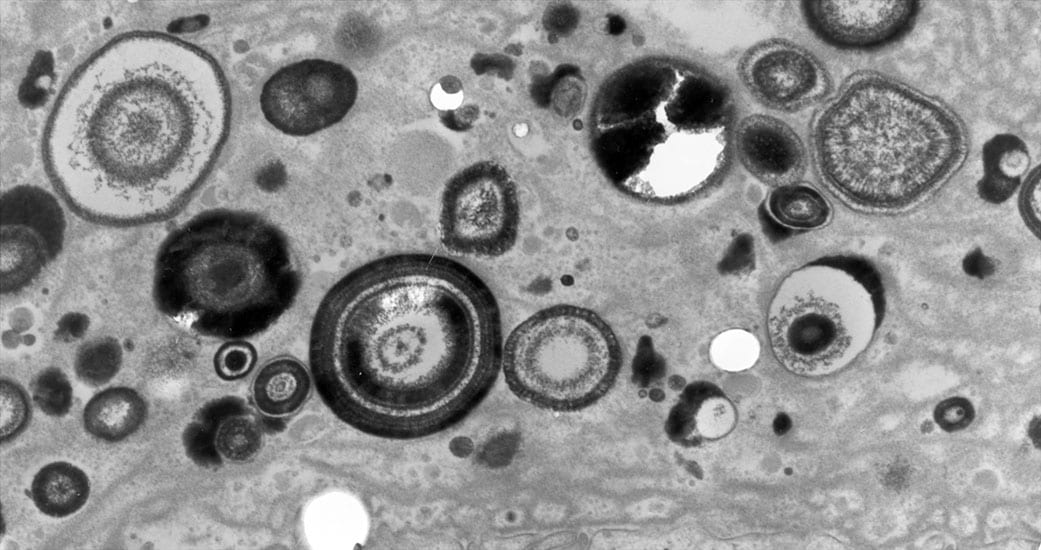

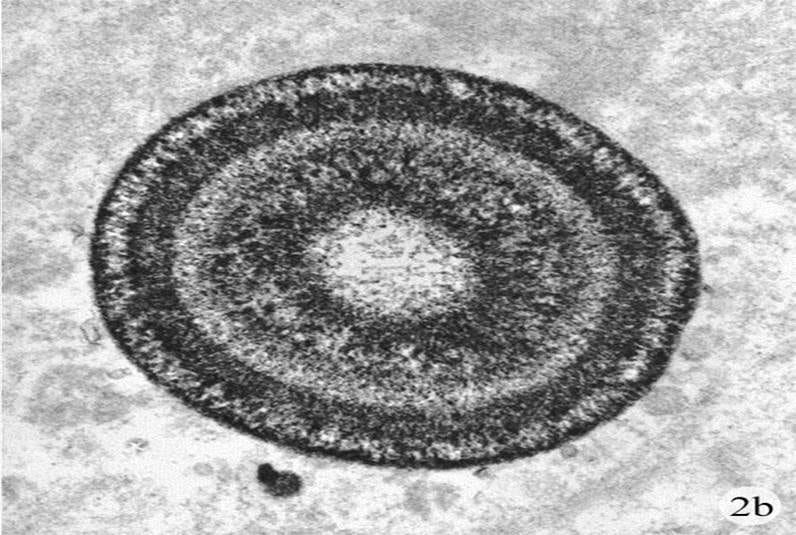

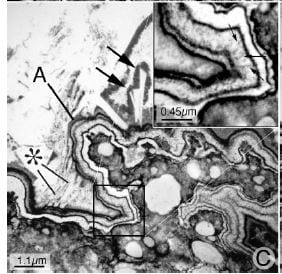

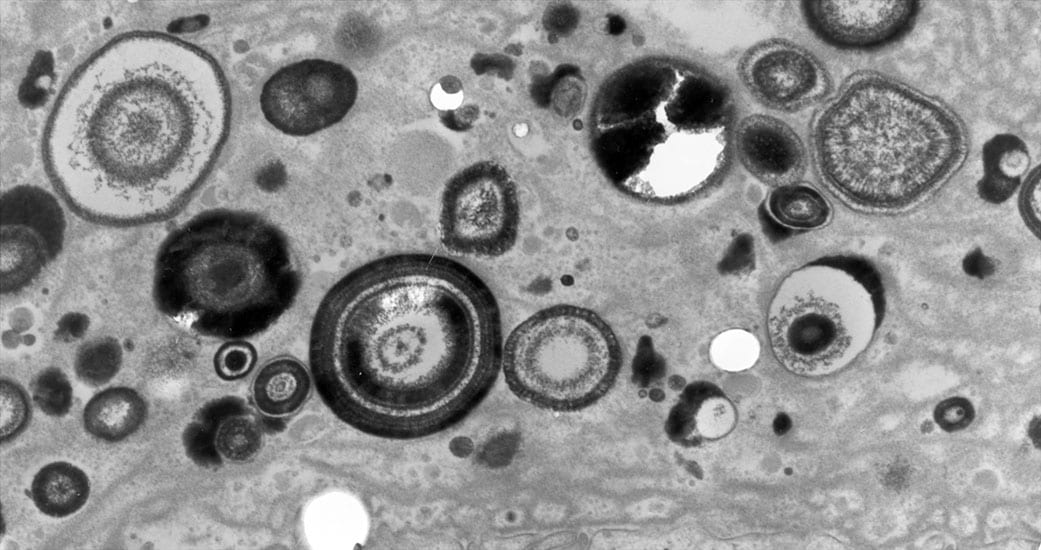

Three Pathways for Kidney Stone Formation All kidney stones share similar presenting symptoms, and urine supersaturation with respect to the mineral phase of the stone is essential for stone formation. These clinical similarities have made it difficult for researchers...

by Andrew Evan | Aug 20, 2016 | For Doctors, For Scientists

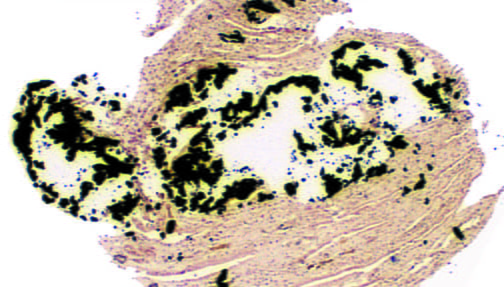

Between stone attacks, one can forget about the importance of prevention. So much water, pills, and nothing happens. This new post shows very new research done over the past decade or so, mainly by us, which shows that the tiny tubules of the kidneys can become plugged with calcium phosphate crystals. Fortunately kidney function appears to remain intact, but there is cell injury and inflammation. No one knows right now if stone prevention treatments will also prevent these plugs, but since the plugs form at the very ends of the renal tubules, where the final urine exits into the renal pelvis, one would think that whatever reduces crystal formation in the urine will reduce plugging.

by Dr Fredric Coe | Jul 28, 2016 | For Doctors, For Patients, For Scientists

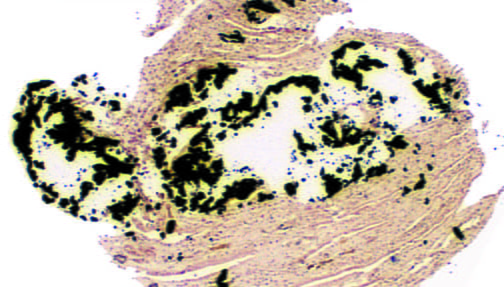

The second in this series of stone forming phenotypes, the calcium phosphate stone formers are less numerous than the calcium oxalate stone formers, but perhaps more worrisome, and certainly more complex. There are two types, those whose stones contain any brushite – an unusual form of calcium phosphate in stones, and those whose phosphate is only hydroxyapatite – the mineral found in bones. This latter group is to a large extent composed of young women, for reasons we do not know. Phosphate stones are likely than the calcium oxalate variety to be numerous, and often produce nephrocalcinosis, a mixture of small stones and tissue calcium deposits. Nephrocalcinosis, in turn, is often labelled medullary sponge kidney simply on radiological grounds, even when the distinctive lesions of MSK are not necessarily present. Likewise, phosphate stone patients can appear to have renal tubular acidosis because of nephrocalcinosis and because RTA and phosphate stone patients both produce a more alkaline urine than do normals, or patients with calcium oxalate stones. All in all, this is a complex form of calcium stones, challenging for clinicians and often very trying and concerning for patients with it. The article is long and difficult, so you might want to watch this video by way of an introduction.