Our site is fortunate that Dr. Luke Reynolds, an outstanding young urological surgeon, has created an article on percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL). Many patients come to need this complex surgery, and most will not know much about it. An article about PCNL has long been missing and I am thrilled this talented and experienced surgeon has been willing to write it for us. Fred Coe

The lovely photograph of autumn’s gourds is by Phyllis Brodny, a contemporary artist to whose eyes these natural shapes display startlingly human attitudes. This image is from the cover of her book of gourds pantomiming life, the commonplace and the wonderful.

Origins of PCNL

Before the 1970’s patients suffering from kidney stones required open surgery. In 1976 Fernström and Johansson described a way to create a tract into the kidney through a small incision in the back. Instruments could be passed through the tract to remove stones. This was the first example of Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL). PCNL has virtually replaced open surgery because it allows removal of even large stones.

Shockwave lithotripsy (SWL) and ureteroscopy (URS), perfected over the past decades, together with PCNL, make up the three main surgeries used for stone removal.

Why PCNL vs SWL or URS?

The straightforward answer is that large kidney stones (greater than 2 cm or 1 inch) are best treated by PCNL as URS and SWL often fail to remove all the stone material leaving behind residual fragments. Shockwave Lithotripsy (SWL) is ideal for one or perhaps a few smaller stones. Ureteroscopy (URS) can remove numerous stones but does poorly when the mass of stone is large. These are the general rules that surgeons tend to follow. Besides stone size and location, the anatomy of the kidney, symptoms, general health and patient expectations all weigh into the final decision.

This last is very important, as patients may well have their own priorities. SWL is the least invasive method and some may prefer it despite a greater chance of residual stone fragments. PCNL may be the ideal in a given situation but patients elect otherwise because the procedure is more invasive. URS stands somewhere in between these extremes. So a shared decision making process is needed between patients and their urologist to choose which treatment is truly right for them.

Benefits of PCNL

Most Likely To Make Kidneys Stone Free

Although PCNL is the most invasive treatment option for kidney stones, apart from the rare open surgery itself, it is the procedure most likely to clear the full stone burden in a single treatment. The American Urology Association guideline recommends, “In symptomatic patients with a total renal stone burden >20 mm, clinicians should offer PCNL as first line therapy”.

A randomized controlled study in 2015 (Karakoyunlu et al.) demonstrated that multiple URS sessions were needed in order to have a similar outcome to a single PCNL. Another finding of this study was that even with multiple treatments, patients still had a higher rate of small residual fragments with URS compared to PCNL. Residual stone fragments can be a problem in the future as they grow larger or cause pain, bleeding, infection, or obstruction.

Specially Good for Lower Pole Stones

Due to anatomy, stones in the lower pole of the kidney pose a particular challenge for surgeons. Fragments from SWL or even URS often lodge there, especially when the original stone was large. As an example, a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that PCNL produced a 95% stone free rate compared to 37% with SWL (Albala 2001).

A recent review article concerning treatment options for lower pole stones, confirmed that PCNL generally provides higher stone free rates compared to both URS and SWL. This is balanced, however, by a longer hospital stay and the potential for complications (Zhang 2015).

Given the trial data, the American Urology Association guidelines recommend, “Clinicians should inform patients with lower pole stones >10 mm in size that PCNL has a higher stone-free rate but greater morbidity”.

For any one patient, the final choice depends on anatomy and stone characteristics, so the choice between URS and PCNL, and even SWL can be complex. As always, patients have a right to add their own priorities into the final decision.

Virtually Required for Staghorn Stones

Unfortunately, some people form exceptionally large branched stones that can fill the entire renal pelvis and calyces. The radiograph at left shows such ‘staghorn‘ stones. They look like the horns of a stag, do they not?

Often times staghorn stones are composed of struvite created by urinary tract infection, and treatment requires skilled surgery and antibiotic treatment combined.

PCNL is the recommended treatment for staghorn stones. SWL and URS have limited success with them. If the stone does contain struvite, and is therefore infected, it’s important to try and completely remove the stone without leaving fragments behind as residual fragments can act a nidus for future stone growth and infection. As well, more common calcium stones can be infected, too, and demand special care.

How PCNL is Performed

Preoperative Assessment

Before undergoing surgery, patients will require routine blood work, a urine sample to rule out infection, and a CT scan to better understand anatomy and stone characteristics. Often times patients will be assessed by an Anesthesiologist to ensure that they can safely undergo a general anesthetic.

Positioning

After going off to sleep, patients are most commonly positioned prone position – lying on their front. This allows access to the kidney with good working space while avoiding the bowel. Recently, some surgeons have placed patients supine – on their back. Surgeons who favor this approach say that stone free rates and overall complications are similar to prone positions, but the supine approach is faster – easier positioning, and may also lead to fewer postoperative fever events (Li 2019).

Renal Access

The most critical step of the procedure is gaining access to the kidney. It was special access that originated PCNL in the first place.

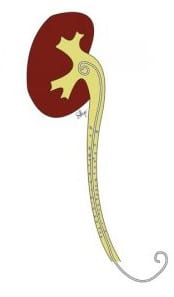

One inserts a needle through the back or flank and guides it into a calyx of the kidney. Once the needle is inserted into the kidney, a working sheath is inserted over a dilator. The working sheath allows the surgeon to insert scopes and instruments to fragment and remove the stones.

One inserts a needle through the back or flank and guides it into a calyx of the kidney. Once the needle is inserted into the kidney, a working sheath is inserted over a dilator. The working sheath allows the surgeon to insert scopes and instruments to fragment and remove the stones.

The drawing shows the sheath passing through the outer part of a kidney and through a papillum into the renal pelvis where a large stone resides. An instrument has been passed through the sheath to break up and remove the stone.

For most surgeons, access is performed under x-ray guidance although it can be performed with ultrasound guidance or a combination of the two. Although more technically challenging, ultrasound guidance limits radiation exposure (Liu 2017).

A third method for gaining access uses ureteroscopy to visualize the needle in real-time as it enters the kidney. The link takes you to a brief and nifty video showing the procedure. Through the optics of the ureteroscope the surgeon can confirm the correct placement of the needle. This decreases the amount of x-ray required. As well, the surgeon can use URS to help treat the stone if needed.

Recently some surgeons have adopted the Miniaturized PCNL approach. Mini PCNL requires the same procedural steps of a standard PCNL, but uses a smaller dilator and working sheath. You can see the size difference in the picture at left. The benefit of Mini PCNL is that smaller dilation decreases the risk of bleeding (Atassi 2019). The major downside is that a smaller sheath may impede removal of larger stones. Although the role of Mini PCNL is evolving, it may be an appropriate option to treat stones <2 cm in size.

Removal of the Stone

Typically, surgeons will use a combination of instruments to perform a PCNL The most useful tool to treat large stones are intracorporeal lithotripters which use a combination of ballistic and ultrasonic wave energy to break the stone into tiny pieces while simultaneously vacuuming out the fragments. The link above is to a brief movie that shows a lithotripter inside a kidney breaking up a large stone during a PCNL.

When intracorporeal lithotripters are unable to reach the stone, surgeons can use a combination of laser lithotripsy and baskets to treat the stone. The laser light has a high temperature and is used to break the stone into small pieces or dust the stone into sand. At the end the scope is pulled back through the sheath and fragments removed from the kidney,

After the stone has been treated, the entire kidney is inspected with flexible nephroscopy to attempt to identify any fragments that may have migrated during the procedure.

Post Surgical Drainage

At the conclusion of the surgery most surgeons will leave a nephrostomy tube, a ureteric stent, or a combination of both to ensure the urine from the kidney drains without obstruction.

A nephrostomy tube drains urine from the kidney through a tube using the tract established from the surgery. The left part of the picture shows the drain and its bag to collect fluid. At the right of the picture, the coiled end of the drain is shown inside the renal pelvis just where the ureter begins.

A ureteric stent is a small flexible tube that drains the urine from kidney, down the ureter to the bladder. The small picture just below shows a stent, Its coiled upper end is much like that of the drain of a nephrostomy tube, but instead of draining out through the skin, it drains into the bladder.

In recent years some surgeons have begun to favor just a ureteric stent. Compared to a nephrostomy tube, a stent may cause less post-operative pain and lung complications, and allow a shorter hospital stay and an earlier return to work (Xun 2017, Alschuler 2019). Regardless of which type of drainage tube is used, both are temporary and often removed within a week.

Post Operative Care and Discharge

Most surgeons aim for discharge after 1 day in hospital. In some centers patients are discharged home the same day of surgery. Compared to those kept overnight, patients selected for “ambulatory” PCNL tend to be healthier, have less complex stone disease, and an uncomplicated operation (Bechis 2018, Schoenfeld 2019).

Complications

Approximately 13% of patients present to emergency departments within a month after surgery (Khanna 2020). Common reasons are voiding discomfort, flank pain, and blood in the urine. More serious risks with PCNL are severe bleeding, and infection. Risk factors for bleeding include longer operative times, larger stones, multiple punctures, hypertension, diabetes and a larger tract size. The risk of bleeding requiring a blood transfusion ranges from 1-10%.

The risk of developing a post-operative infection following PCNL ranges from 2.5 – 20%. This variability is in part due the nature of the surgery and the fact that many stones are infected. Patients with bacteria in their urine pre-operatively require a full course of antibiotics prior to surgery to try and prevent post-operative fever. Patients are monitored post-operatively for signs of infection (fever, elevated heart rate, low blood pressure) and treated as needed.

Follow-up

Most surgeons will obtain a CT scan or a plain x-ray and ultrasound to visualize residual stones and rule out obstruction. Sometimes residual stones need to be treated, some can be observed over time. The count of residual stones is crucial to assess whether new stones are forming once medical stone prevention is in place. All removed stones and fragments must be analysed as this is crucial for long term prevention.

SUMMARY

- Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy is a well-established treatment for large kidney stones.

- The aim of PCNL is to remove all of the stone burden with a single treatment

- The most common reasons for PCNL are stones >2 cm and lower pole kidney stones >1cm.

- Most patients will be home 1 day after surgery.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

Q: Does the dilation of the kidney cause long-term damage to the kidney?

A: Following your surgery it is not uncommon to see a transient decrease in renal function. Over time, renal function typically returns to normal and can even improve, particularly if the stone was obstructing the flow of urine.

Q: What happens to the tract in the kidney after the procedure?

A: After the working sheath is removed the tract closes up on its own. Urine leak from the back is possible and typically resolves after a day or two.

Q: Do the tubes and stents cause pain?

A: The nephrostomy tube typically does not cause pain (although can be uncomfortable) but it does require that you carry around a drainage bag to collect the urine. The ureteric stent is often uncomfortable – commonly patients experience urinary frequency, urgency and blood in the urine while the stent is in place. Your symptoms will improve after the stent is removed.

Q: Do I need to stop my anticoagulation (blood thinner) before surgery?

A: Most surgeons will NOT perform a PCNL if you are taking medication to thin your blood. Before stopping blood thinners it is necessary to speak with the anesthesiologist or doctor who prescribed the medication to ensure that it is safe.

Q: How big will my scar be?

A: The incision on the back/flank is about an inch in size

Q: When will I be able to return to work?

A: Everyone recovers at their own pace, however, most patients will be able to return to work about a week after their procedure.

A very good and clear article by Dr. Luke Reynolds on PCNL and kidney stone removal in general. I very much admire Dr. Reynolds for his work and his high energy and expertise in helping patients with kidney stones. And, thanks to Dr. Coe for having this article on his venue.

Thank you very much.

Ted Meredith

Gainesville, GA

Hi Ted, Thanks for the comment. I was very happy to have Luke on the site. Regards, Fred

This article is very helpful to m as a layman trying to understand the risks that PCNL poses for me as one who has bEven recommended for this procedure for a 27 mm stone lodged in the left lower pole. I feel that I have had to take “ control” of the steps that , I believe, should be done to make a knowledgeable decision of this predation vs. the other 2techniques , beginning with requesting that my doctor order the 24 hour urine to possibly determine what type of stone this is and what the other stones scattered about are composed. If it (they) are of a dissolvable nature, then i would do a massive dietary and fluid intake to , at the least, see if it could be shrunk in size or even dissolved. Or can i as a 73 year old live a somewhat comfortable life,and learn to retrain my bladder. Having had 1 URS as a 40 year old , followed by 3 self passings and a prostate( 139 cc) urolift surgery, i feel that i am facing a less than optimal bladder situation playing into urgency and frequency.

I look forward to a weigh – in on why large amounts of water intake (2250 ml) may not be what you, as doctoR , may suggest.

Hi Tom, Prevention always matters – here is a good article on the steps required. As for PCNL, the stone is large enough and if it is obstructing, or causing pain, infection, or obstruction it needs to come out. If not, just there, it is not urgent to remove it until prevention is in place – to avoid rapid new growth. Large amounts of water are not always needed so much as reversal of all of the stone causes. Take a look at the article and get tested. Regards, Fred Coe

This article is very helpful to m as a layman trying to understand the risks that PCNL poses for me as one who has been recommended for this procedure for a 27 mm stone lodged in the left lower pole. I feel that I have had to take “ control” of the steps that , I believe, should be done to make a knowledgeable decision of this procedure vs. the other 2 techniques . I began with requesting that my doctor order the 24 hour urine to possibly determine what type of stone this is and what the other stones scattered about are composed. If it (they) are of a dissolvable nature, then i would do a massive dietary and fluid intake to , at the least, see if it could be shrunk in size or even dissolved. Or can i as a 73 year old live a somewhat comfortable life,and learn to retrain my bladder. Having had 1 URS as a 40 year old , followed by 3 self passings and a prostate( 139 cc) urolift surgery, i feel that i am facing a less than optimal bladder situation playing into urgency and frequency as an end result.

I look forward to a weigh – in on why large amounts of water intake (2250 ml) may not be what you, as doctor, suggest.

Hi Tom, I think this is a repeat of your other question. But it has a slight difference. The CT density of the stone can help determine if the stones are uric acid – low HU. If so they can be dissolved by raising urine pH and this could be important to you. See what the density is. Regards, Fred Coe

Thank you for insightful article. I realize what your suggestion would be for a 28 mm lower pole stone. I am still not over the fear of complications and risk factors. I d appreciate a follow up on this from a patient’s point of view.

Kidney stones and nephrolithotomy are a sore subject for me. I went through almost 6 months of nephrostomy tubes while pregnant with my first while in the army active duty. Over 40 procedures were performed, while still working most of it. The final surgery was 12 weeks after he was born, when they removed the 4 stones a cm a piece. I absolutely loved my medical team and docctors, who were great at their job and aided me as best they could in comfortability. The great thing about it was that the procedures didn’t last but 5 minutes max. The scarring is also minimal compared to fully cutting open the kideny, which ,I also unfortunately experienced when I was 11, due to 9 kidney stones and a upj obstruction. If stones are quite large, this could be a better option for patients than shockwaves.

Hi Dr. Coe,

I have just located this site. I came to it looking for answers. My twin sister and I have suffered from Kidney stones since our twenties. We are now 63. We were told that we both have medullary sponge kidney. (So ours must be congenital and yes I think we have other genetic disorders in our family like Marfan syndrome ) I have passed many stones during this time. I only ever had one removed (the first one). My sister has had several procedures done . At this time, I have been passing more and she hasn’t passed any in quite awhile. I haven’t been to a urologist lately but with this recent episode, I have an appt. in about 2 weeks. I am interested in this procedure, PCNL, if it can make me kidney stone free. Do you know anyone in the NY/NJ area that does this procedure?

Thank you,

Sharon Gianneschi

Hi Sharon, The perc is a big procedure, and one does it because of pain, bleeding, infection or obstruction. Stone prevention in NY is Dr David Goldfarb, a superb expert. He is at NYU.I would use him for guidance as to local urological surgery experts and stone prevention. Regards, Fred Coe

I am going for this procedure in a few weeks so very scared! If anyone has had it and can share the experience with me I would be so grateful 🙏

Hi Susan,

I have a very supportive group on Facebook that you might find very helpful for all things kidney stones. It is monitored by me so that the info is clinically correct.https://www.facebook.com/groups/kidneystonediet/?ref=bookmarks

Best, Jill

Question: Is a plug ever used to plug the hole in the kidney after the sheath is removed? If so, is this plug biodegradable, or will it stay in the kidney wall forever? What happens if the plug dislodges, e.g., during strenuous exercise? Asking for my spouse who loves a good workout on the treadmill.

Hi Patricia, I presume the sheath refers to that put up the ureter during ureteroscopy. If that is what is at issue, the kidney drains urine down the ureter to the bladder, so there is no hole. The instrument is passed up the ureter from the bladder into the kidney and then removed. Fred

I am a stone former and have a very unusual anatomy. I’ve had three surgeries in the past with ureteroscopy (3 to 4 mm calcium oxylate stones each time). I have four fully formed kidneys, two per side, and they each have their own ureter going down to the bladder. I’ve been told my ureters are unusually narrow and that it would be very unlikely that any of my stones (even very small ones) could pass, without requiring surgery. A recent CT scan found one of my right side kidneys has a 3mm stone, the other right side kidney has two 1mm stones, and one of the left kidneys has a 1mm stone forming. I’d rather not wait till the larger 3mm stone breaks loose and requires emergency surgery. I’d prefer elective surgery to avoid all the pain and nausea that results from the stone getting stuck in one of my ureters. Would this type of surgery ever be appropriate in my situation?

Hi Robert, You do indeed pose a special kind of surgical problem. My only suggestion is for your physicians to arrange referral to a specialized stone surgery center. Possibly ureteroscopy would work using pediatric size instruments, that is a wild guess. You need the rare surgeon who has worked this kind of issue and can perhaps help. I should mention, stone prevention is of maximal importance to you so I presume you are doing everything possible. Here is a good start. Regards, Fred Coe

Thanks for the great article. I have a stone that appears to be ~ 23mm. I have no pain, no obstruction or no issues (it happened to show up on an x-ray for something totally unrelated). Are there other options for a stone of this size given it is not causing any issues at the moment besides PCNL? Candidly, the idea of the surgery, the stent and the recovery is really daunting and worrisome. Thanks!

Hi David, I presume it is not uric acid – one would know from the density on CT scan. Likewise, is it possibly cystine? If a calcium stone, alas, PERC is most likely your only way – URS is too small scale to get rid of stones that large and shock wave is going to just leave a lot of fragments. I presume your urologist has chosen PERC. Find out why you made the stone so as to prevent another. Regards, Fred Coe

My 69 y.o. otherwise healthy wife just had a 22mm stag horn located R renal pelvis removed with “mini” PCNL two days ago and is still admitted with unbelievable pain. CXR and abdominal ultrasound clear, ureteric stent in place and appears to be draining well. Foley out today. Her pain level is so high that she needs opiates which knock her out. Blood cultures were drawn last night as were done preop (negative) and with the exception of abnormally low blood pressure, her remaining vital signs appear wnl. This post op course seems a bit unusual, no?

Hi William, Not so much – although I am not a surgeon. The low blood pressure must have worried her physicians – sign of sepsis? – but by now that will have been a settled issue. The degree of pain is higher than I have heard about from patients, but surgery pain is variable among people. I hope the stone was analyzed, and she plans on prevention. Here is a good start for her. Regards, Fred Coe